FormativeForces explores how a plant’s properties and historical migrations can inspire new craft practices linking nature and culture. Focusing on wild hop (Humulus lupulus), a migratory plant that settled in the Lower Oder River Valley, the project uses a natural retting process to obtain rare, sustainable fiber. This fiber’s unique qualities guided the crafting of bobbin lace, a migratory textile technique introduced to Poland in the 16th century. The work intertwines botanical specificity and cultural history, proposing a making process led by attentiveness to materials, ecologies, and heritage.

The project is presented at the Material Matters exhibition, taking place in the Space House during the London Design Festival 2025.

Formative Forces emerged from research developed within the annual program Local Bio-based Materials by The Material Way, a collective platform for material-based studies that brings together artists and researchers dedicated to crafting a more holistic, local, and nature-oriented future. The platform was founded by curator Rita Trindade (Through Objects) and multidisciplinary designer Bonnie Hvillum (Natural Material Studio).

Photos: Peter Oliver Wolff

Project description

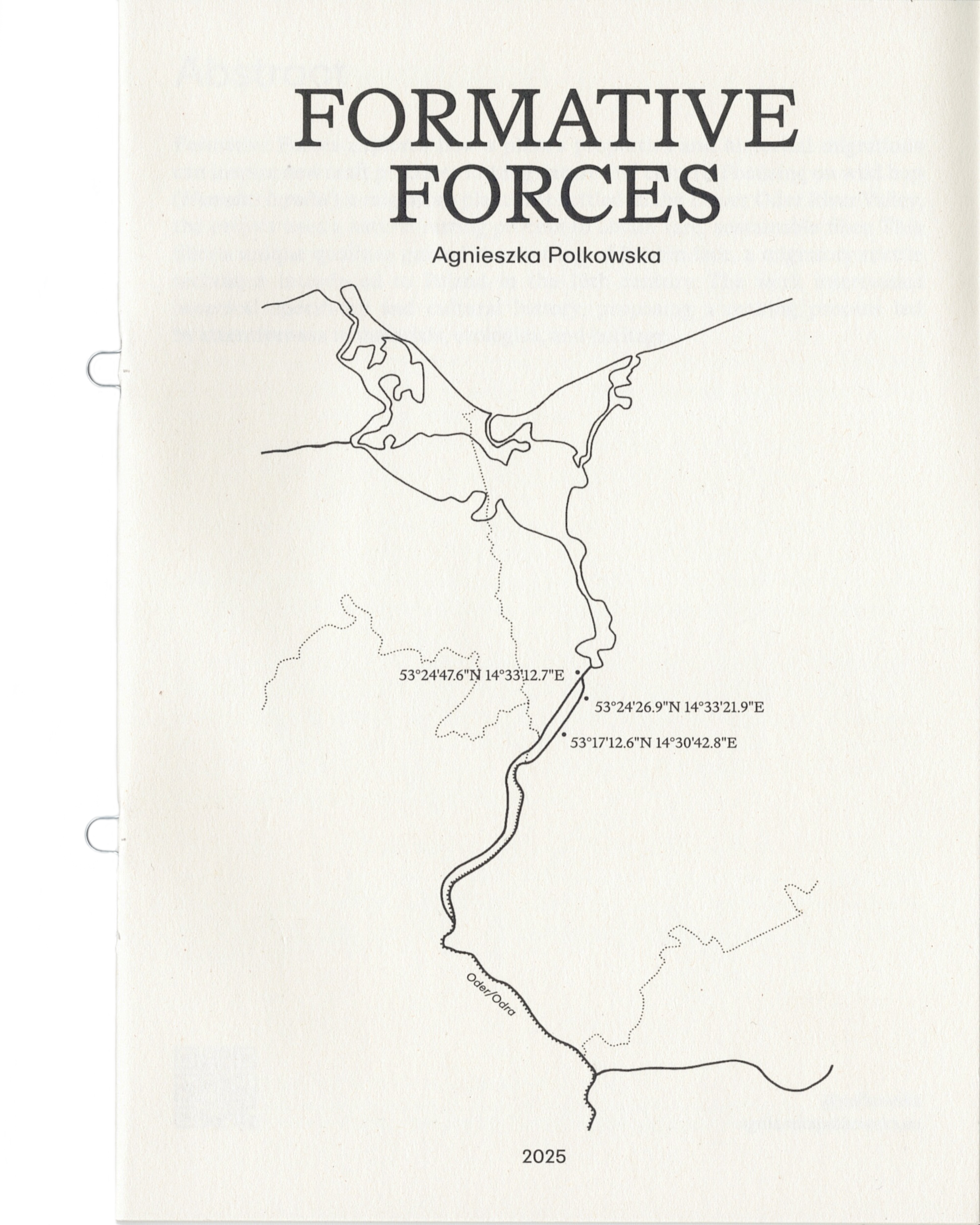

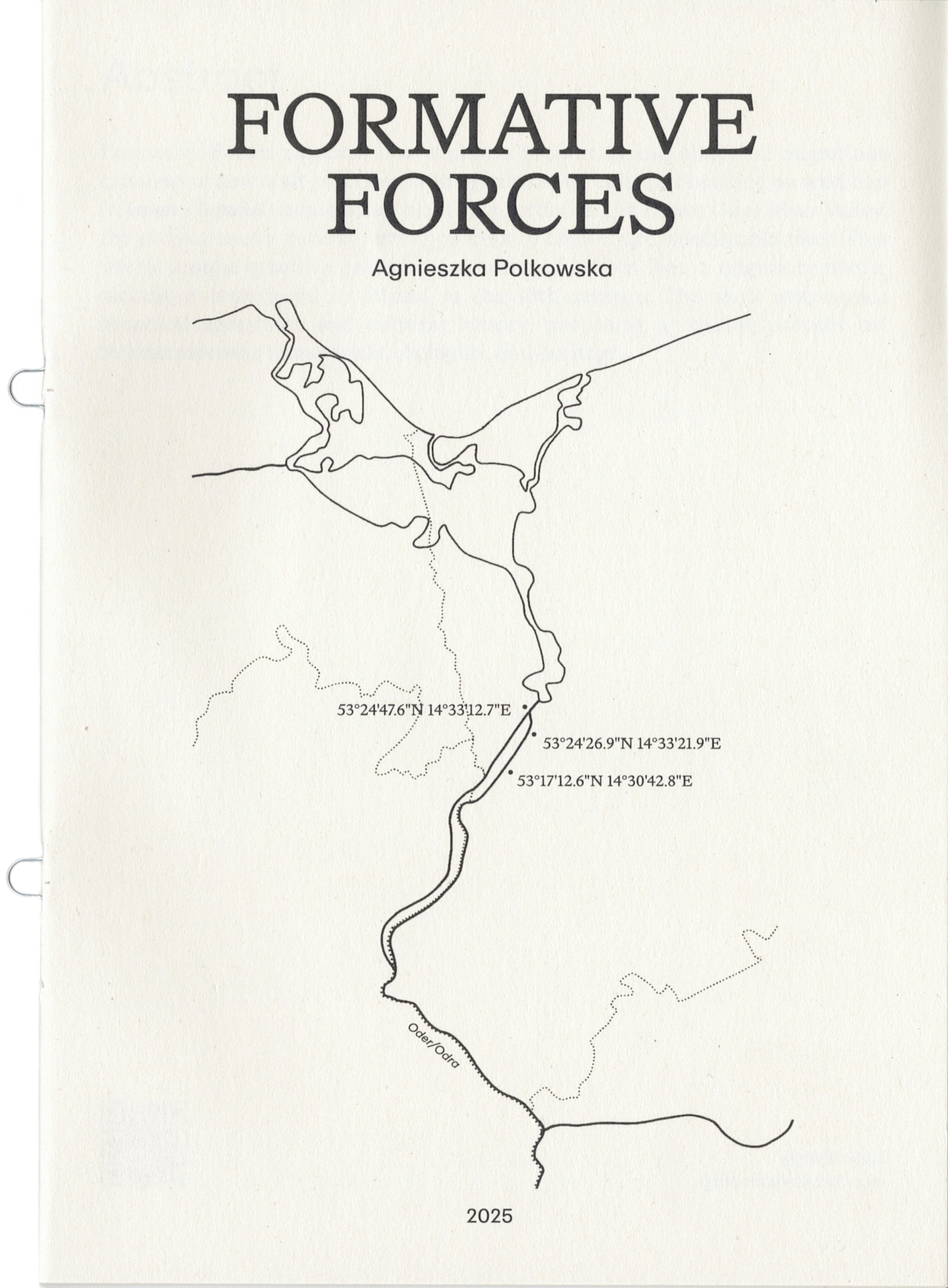

Formative Forces is a material-led research project rooted in the riparian forest of the Lower Oder River Valley, near Stettin — a city shaped by post-war migrations and cultural overlays. In this project, I explore how a plant’s inherent properties can inform craft practices that weave together the layered history of place with the rhythms of adaptation found in both nature and culture.

The investigation centers on wild hop (Humulus lupulus) — a migratory plant that settled in this region due to favorable living conditions. Unlike cultivated varieties, which are exclusively female and selected for brewing, wild male hop plants offer particularly fine fibers. I extract these through a fully natural retting process. This approach relies on time and environmental decomposition, requiring no industrial inputs and causing no harm to living plants.

The result is a rare and sustainable fiber, available in very limited quantities. These constraints guided the craft approach. The fibers’ structure, high lignin ¹, and resemblance to hemp directed me toward traditional textile methods unsuitable for industrial use but ideal for small-scale, sensitive work. The final material outcome is bobbin lace made entirely from wild hop fiber.

Just as wild hop is a migratory plant, bobbin lace is a migratory technique — brought to Poland from Italy by Queen Bona Sforza in the 16th century. The intertwining of these two "migrants" — plant and method — forms a dialogue between natural adaptation and cultural transmission. The lace-making process itself mirrors how wild hop twines around neighboring plants and old stems ², recreating this gesture through handcraft.

The resulting work fuses migratory history, botanical specificity, and traditional craftsmanship — bridging natural rhythms with cultural memory. Formative Forces proposes a form of making led not by control, but by attentiveness — allowing materials, histories, and ecologies to guide the hand and shape meaning.

¹ 0 +/- 0,2% compared to 2–5% in hemp (Reddy & Yang, 2009)

² The term lupulus comes from Latin and means "little wolf." This name was given because the plant often wraps itself around and smothers other vegetation in a way similar to how a wolf might attack a sheep.

Full research description in the → booklet.

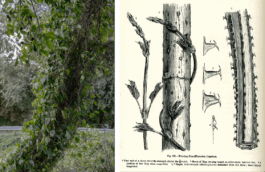

Wild hop natural habitat: Riparian Forest in the Lower Oder Valley

Wild Hop – From Plant to Thread

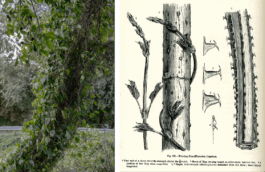

"Little wolf"

The term lupulus comes from Latin and means "little wolf." This name was given because the plant often wraps itself around and smothers other vegetation, especially basket willows, in a way similar to how a wolf might attack a sheep. Hops were frequently seen climbing over these willows, which led to the nickname "willow-wolf".

Source of illustration: Kerner von Marilaun, A. (1895). Humulus lupulus [Twining hop]. In Natural history of plants. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal.

Decay-growth Cycle

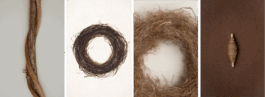

The process of obtaining fibers mirrors the natural cycle of decay and growth, where decomposition is not an end but a condition for renewal. Fungi and bacteria initiate this cycle, making new growth—or usable fiber—possible. Natural retting is a highly sustainable method, relying solely on wild stems that have undergone these processes without industrial inputs or chemical treatments, or the use of living plants.Stems are collected after winter, having passed through stages of microbial and fungal decomposition. Unlike traditional dew retting, this process unfolds entirely in the wild without the need for human labor. By depending exclusively on what would naturally decompose or be shed from the habitat, the environmental impact is minimal, while the quality of the fiber is maximized. In this sense, natural retting is not merely eco-friendly and chemical-free; it is a natural process that shapes my practice—work attuned to the rhythms nature—a small-scale, inherently precious way of engaging with what the world already offers.

Marder (2020)¹, emphasizes that destruction and renewal are intertwined, and that the processes of decay themselves create the conditions for new forms of being—a perspective that resonates material transformation explored in this project.

¹ Marder, M. (2020).Dump philosophy: A phenomenology of devastation. Bloomsbury Academic.

From Hop-stem to Thread

The fibers of the hop are located beneath the epidermis, in the outer layers of the stem. To extract and prepare them for spinning into thread, they need to undergo several stages of processing.

1. Peeling & scutching

2. Hackling

3. Hand-carding

4. Hand-spinning

Why Craft?

Honoring the Nature of the Plant

The craft approach arises naturally from the unique qualities of the wild hop plant. While cultivated common hop varieties are exclusively female and grown for brewing, it is the male plants that offer particularly fine fibers. These male plants, found only in the wild, have almost never been intentionally cultivated — aside from a few known attempts in 18th- and 19th-century Sweden¹. Belonging to the same botanical family as hemp, hop fibers share many similar properties, but their higher lignin content (around 6.0 ± 0,2% compared to 2–5% in hemp)² makes them unsuitable for sustainable industrial processing. The small amount of fiber that can be extracted—roughly one small ball of thread per square meter of retted stems—further emphasizes its value. As such, this rare, high-quality material is best honored through traditional craft techniques, which respect both the plant’s nature and its ecological context.

¹ Skoglund, G., Holst, B., & Lukešová, H. (2020). First experimental evidence of hop fibres in historical textiles. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12(214).

² Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2009). Properties of natural cellulose fibers from hop stems. Carbohydrate Polymers, 77(3), 532–538.

The migration of lace-making techniques across Europe

All lace-making techniques most likely date back to Antiquity, when people sought ways to reinforce and protect clothing from wear and tear. At first, they were connected with net-making. Later, the technique was likely adapted for a different purpose, and this is how lace began to evolve. Bobbin lace itself is believed to have originated in Italy, most likely in Venice, developing out of needle lace.

The art of lace developed gradually. The 16th and 17th centuries marked a period of flourishing lace-making. A beautifully crafted piece of lace could be worth as much as three villages, as it was extremely valuable due to the time and skill required to create it. Not everyone possessed the necessary knowledge or ability, and the threads themselves were costly. In the 19th century, with the rise of machine production of both threads and lace—thanks to specially designed lace-making machines—lace became more accessible and lost its status as an exclusive material.

Just as wild hop migrated into Poland from the East, bobbin lace was introduced to Poland by Queen Bona Sforza, a member of the Milanese Sforza family. The Sforza family’s will contains the first known reference to lace made with twelve bobbins¹. However, Poland did not initially develop a distinctive lace-making style of its own. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that the first lace school in Poland was founded in Zakopane by Helena Modrzejewska. A second school was later established in Bobowa, which today is a renowned center for bobbin lace. Modrzejewska designed patterns inspired by Polish flora and fauna, particularly plant motifs drawn from the lace-makers’ local environment².

¹ de la Guardia, C. (n.d.). Milanese lace. Retrieved August 22, 2025, from https://www.carolgallego.com/el-rincon-del-encaje-de-bolillos/lace-lacemaking/lace-history/milanese-lace

² Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. (2010, Ausgust 13). Recreated patterns of Zakopane bobbin lace [Odtworzone wzory – wprowadzenie]. Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa.

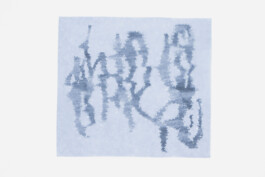

Lace pattern

The lace pattern developed within the Formative Forces project originates from a sketch that traces the gestures of wild hop and the forms it generates in its natural habitat. As the hop fiber thread hooks onto pins, it extends into rhizome-like structures, mirroring the plant’s way of clinging to and entwining itself around other vegetation. In this way, the act of lace-making reimagines the hop’s own strategies of attachment and growth, translating them into textile form.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the people who made this research project possible, as well as those who supported its development:

_ Sarmite Polakova, Alberte Holmø Bojesen, Benedetta Pompili, Rita Trindade, and Bonnie Hvillum at The Material Way

_ Aleksandra Sobieszczuk, from the Studio of Traditional Crafts and the Polish Chamber of Heritage Crafts in the West Pomeranian region of Poland

_ Git Skoglund, textile researcher and ethnologist, fellow at Agnes Geijer Nordic textile Research Foundation

_ Peter Oliver Wolff, photographer

Resources

Agbo-Ola, Y. (2025, May 14). Matter asked to be gas, as rivers became solid [Lecture]. The Material Way.

Bastian, E. (2025). Welcome to working with hop fibres [Lecture]. Plants & Colour.

Dodge, C. (1908). A descriptive catalogue of useful fiber plants of the world: Including the structural and economic classifications of fibers. Government Printing Office.

de la Guardia, C. (n.d.). Milanese lace. Retrieved August 22, 2025, from https://www.carolgallego.com/el-rincon-del-encaje-de-bolillos/lace-lacemaking/lace-history/milanese-lace

Kerner von Marilaun, A. (1895). Humulus lupulus [Twining hop]. In Natural history of plants. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal.

Kozlowski, R. M., & Mackiewicz, M. (Eds.). (2020). Handbook of natural fibres: Volume 2: Processing and applications(Vol. 2). Woodhead Publishing.

Marder, M. (2013). Plant-thinking: A philosophy of vegetal life. Columbia University Press.

Marder, M. (2020). Dump philosophy: A phenomenology of devastation. Bloomsbury Academic.

Marder, M. (2025, June 25). Waste. Follow up to “Dump Philosophy: A Phenomenology of Devastation” [Lecture]. The Material Way.

Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2009). Properties of natural cellulose fibers from hop stems. Carbohydrate Polymers, 77(3), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.03.013

Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2015). Fibers from hop stems. In N. Reddy & Y. Yang (Eds.), Innovative biofibers from renewable resources (pp. 43–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-45136-6_12

Rzeszotarska-Pałka, M. (2012). The tradition of vineyards in the area of Western Pomerania. Czasopismo Techniczne. Architektura, 109(30), 8-A. Wydawnictwo PK.

Skoglund, G. (2021). Traditional manufacture of hemp and hop textiles: Why botany and agronomy matter. Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology, 9(1), 1–16.

Skoglund, G., Holst, B., & Lukešová, H. (2020). First experimental evidence of hop fibres in historical textiles. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12, 214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01171-6

Skoglund, G., Suomela, J. A., & Räisänen, R. (2025). A heritage “nettle” sheet reveals the first physical evidence of a hemp/hop textile from Denmark. Textile. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2024.2439707

Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. (2010, August 13). Recreated patterns of Zakopane bobbin lace [Odtworzone wzory – wprowadzenie]. Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. https://koronkaklockowa.wordpress.com/2010/08/23/

Zee, M. (2023). The effect of different retting methods on hop (H. lupulus) fiber quality for small-scale textile production(Master’s thesis, University of Idaho, College of Graduate Studies).

FormativeForces explores how a plant’s properties and historical migrations can inspire new craft practices linking nature and culture. Focusing on wild hop (Humulus lupulus), a migratory plant that settled in the Lower Oder River Valley, the project uses a natural retting process to obtain rare, sustainable fiber. This fiber’s unique qualities guided the crafting of bobbin lace, a migratory textile technique introduced to Poland in the 16th century. The work intertwines botanical specificity and cultural history, proposing a making process led by attentiveness to materials, ecologies, and heritage.

The project is presented at the Material Matters exhibition, taking place in the Space House during the London Design Festival 2025.

Formative Forces emerged from research developed within the annual program Local Bio-based Materials by The Material Way, a collective platform for material-based studies that brings together artists and researchers dedicated to crafting a more holistic, local, and nature-oriented future. The platform was founded by curator Rita Trindade (Through Objects) and multidisciplinary designer Bonnie Hvillum (Natural Material Studio).

Photos: Peter Oliver Wolff

Project description

Formative Forces is a material-led research project rooted in the riparian forest of the Lower Oder River Valley, near Stettin — a city shaped by post-war migrations and cultural overlays. In this project, I explore how a plant’s inherent properties can inform craft practices that weave together the layered history of place with the rhythms of adaptation found in both nature and culture.

The investigation centers on wild hop (Humulus lupulus) — a migratory plant that settled in this region due to favorable living conditions. Unlike cultivated varieties, which are exclusively female and selected for brewing, wild male hop plants offer particularly fine fibers. I extract these through a fully natural retting process. This approach relies on time and environmental decomposition, requiring no industrial inputs and causing no harm to living plants.

The result is a rare and sustainable fiber, available in very limited quantities. These constraints guided the craft approach. The fibers’ structure, high lignin ¹, and resemblance to hemp directed me toward traditional textile methods unsuitable for industrial use but ideal for small-scale, sensitive work. The final material outcome is bobbin lace made entirely from wild hop fiber.

Just as wild hop is a migratory plant, bobbin lace is a migratory technique — brought to Poland from Italy by Queen Bona Sforza in the 16th century. The intertwining of these two "migrants" — plant and method — forms a dialogue between natural adaptation and cultural transmission. The lace-making process itself mirrors how wild hop twines around neighboring plants and old stems ², recreating this gesture through handcraft.

The resulting work fuses migratory history, botanical specificity, and traditional craftsmanship — bridging natural rhythms with cultural memory. Formative Forces proposes a form of making led not by control, but by attentiveness — allowing materials, histories, and ecologies to guide the hand and shape meaning.

¹ 0 +/- 0,2% compared to 2–5% in hemp (Reddy & Yang, 2009)

² The term lupulus comes from Latin and means "little wolf." This name was given because the plant often wraps itself around and smothers other vegetation in a way similar to how a wolf might attack a sheep.

Full research description in the → booklet.

Wild hop natural habitat: Riparian Forest in the Lower Oder Valley

Wild Hop – From Plant to Thread

"Little wolf"

The term lupulus comes from Latin and means "little wolf." This name was given because the plant often wraps itself around and smothers other vegetation, especially basket willows, in a way similar to how a wolf might attack a sheep. Hops were frequently seen climbing over these willows, which led to the nickname "willow-wolf".

Source of illustration: Kerner von Marilaun, A. (1895). Humulus lupulus [Twining hop]. In Natural history of plants. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal.

Decay-growth Cycle

The process of obtaining fibers mirrors the natural cycle of decay and growth, where decomposition is not an end but a condition for renewal. Fungi and bacteria initiate this cycle, making new growth—or usable fiber—possible. Natural retting is a highly sustainable method, relying solely on wild stems that have undergone these processes without industrial inputs or chemical treatments, or the use of living plants.Stems are collected after winter, having passed through stages of microbial and fungal decomposition. Unlike traditional dew retting, this process unfolds entirely in the wild without the need for human labor. By depending exclusively on what would naturally decompose or be shed from the habitat, the environmental impact is minimal, while the quality of the fiber is maximized. In this sense, natural retting is not merely eco-friendly and chemical-free; it is a natural process that shapes my practice—work attuned to the rhythms nature—a small-scale, inherently precious way of engaging with what the world already offers.

Marder (2020)¹, emphasizes that destruction and renewal are intertwined, and that the processes of decay themselves create the conditions for new forms of being—a perspective that resonates material transformation explored in this project.

¹ Marder, M. (2020).Dump philosophy: A phenomenology of devastation. Bloomsbury Academic.

From Hop-stem to Thread

The fibers of the hop are located beneath the epidermis, in the outer layers of the stem. To extract and prepare them for spinning into thread, they need to undergo several stages of processing.

1. Peeling & scutching

2. Hackling

3. Hand-carding

4. Hand-spinning

Why Craft?

Honoring the Nature of the Plant

The craft approach arises naturally from the unique qualities of the wild hop plant. While cultivated common hop varieties are exclusively female and grown for brewing, it is the male plants that offer particularly fine fibers. These male plants, found only in the wild, have almost never been intentionally cultivated — aside from a few known attempts in 18th- and 19th-century Sweden¹. Belonging to the same botanical family as hemp, hop fibers share many similar properties, but their higher lignin content (around 6.0 ± 0,2% compared to 2–5% in hemp)² makes them unsuitable for sustainable industrial processing. The small amount of fiber that can be extracted—roughly one small ball of thread per square meter of retted stems—further emphasizes its value. As such, this rare, high-quality material is best honored through traditional craft techniques, which respect both the plant’s nature and its ecological context.

¹ Skoglund, G., Holst, B., & Lukešová, H. (2020). First experimental evidence of hop fibres in historical textiles. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12(214).

² Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2009). Properties of natural cellulose fibers from hop stems. Carbohydrate Polymers, 77(3), 532–538.

The migration of lace-making techniques across Europe

All lace-making techniques most likely date back to Antiquity, when people sought ways to reinforce and protect clothing from wear and tear. At first, they were connected with net-making. Later, the technique was likely adapted for a different purpose, and this is how lace began to evolve. Bobbin lace itself is believed to have originated in Italy, most likely in Venice, developing out of needle lace.

The art of lace developed gradually. The 16th and 17th centuries marked a period of flourishing lace-making. A beautifully crafted piece of lace could be worth as much as three villages, as it was extremely valuable due to the time and skill required to create it. Not everyone possessed the necessary knowledge or ability, and the threads themselves were costly. In the 19th century, with the rise of machine production of both threads and lace—thanks to specially designed lace-making machines—lace became more accessible and lost its status as an exclusive material.

Just as wild hop migrated into Poland from the East, bobbin lace was introduced to Poland by Queen Bona Sforza, a member of the Milanese Sforza family. The Sforza family’s will contains the first known reference to lace made with twelve bobbins¹. However, Poland did not initially develop a distinctive lace-making style of its own. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that the first lace school in Poland was founded in Zakopane by Helena Modrzejewska. A second school was later established in Bobowa, which today is a renowned center for bobbin lace. Modrzejewska designed patterns inspired by Polish flora and fauna, particularly plant motifs drawn from the lace-makers’ local environment².

¹ de la Guardia, C. (n.d.). Milanese lace. Retrieved August 22, 2025, from https://www.carolgallego.com/el-rincon-del-encaje-de-bolillos/lace-lacemaking/lace-history/milanese-lace

² Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. (2010, Ausgust 13). Recreated patterns of Zakopane bobbin lace [Odtworzone wzory – wprowadzenie]. Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa.

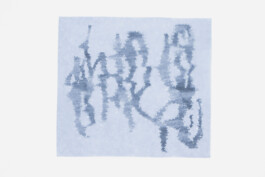

Lace pattern

The lace pattern developed within the Formative Forces project originates from a sketch that traces the gestures of wild hop and the forms it generates in its natural habitat. As the hop fiber thread hooks onto pins, it extends into rhizome-like structures, mirroring the plant’s way of clinging to and entwining itself around other vegetation. In this way, the act of lace-making reimagines the hop’s own strategies of attachment and growth, translating them into textile form.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the people who made this research project possible, as well as those who supported its development:

_ Sarmite Polakova, Alberte Holmø Bojesen, Benedetta Pompili, Rita Trindade, and Bonnie Hvillum at The Material Way

_ Aleksandra Sobieszczuk, from the Studio of Traditional Crafts and the Polish Chamber of Heritage Crafts in the West Pomeranian region of Poland

_ Git Skoglund, textile researcher and ethnologist, fellow at Agnes Geijer Nordic textile Research Foundation

_ Peter Oliver Wolff, photographer

Resources

Agbo-Ola, Y. (2025, May 14). Matter asked to be gas, as rivers became solid [Lecture]. The Material Way.

Bastian, E. (2025). Welcome to working with hop fibres [Lecture]. Plants & Colour.

Dodge, C. (1908). A descriptive catalogue of useful fiber plants of the world: Including the structural and economic classifications of fibers. Government Printing Office.

de la Guardia, C. (n.d.). Milanese lace. Retrieved August 22, 2025, from https://www.carolgallego.com/el-rincon-del-encaje-de-bolillos/lace-lacemaking/lace-history/milanese-lace

Kerner von Marilaun, A. (1895). Humulus lupulus [Twining hop]. In Natural history of plants. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal.

Kozlowski, R. M., & Mackiewicz, M. (Eds.). (2020). Handbook of natural fibres: Volume 2: Processing and applications(Vol. 2). Woodhead Publishing.

Marder, M. (2013). Plant-thinking: A philosophy of vegetal life. Columbia University Press.

Marder, M. (2020). Dump philosophy: A phenomenology of devastation. Bloomsbury Academic.

Marder, M. (2025, June 25). Waste. Follow up to “Dump Philosophy: A Phenomenology of Devastation” [Lecture]. The Material Way.

Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2009). Properties of natural cellulose fibers from hop stems. Carbohydrate Polymers, 77(3), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.03.013

Reddy, N., & Yang, Y. (2015). Fibers from hop stems. In N. Reddy & Y. Yang (Eds.), Innovative biofibers from renewable resources (pp. 43–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-45136-6_12

Rzeszotarska-Pałka, M. (2012). The tradition of vineyards in the area of Western Pomerania. Czasopismo Techniczne. Architektura, 109(30), 8-A. Wydawnictwo PK.

Skoglund, G. (2021). Traditional manufacture of hemp and hop textiles: Why botany and agronomy matter. Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology, 9(1), 1–16.

Skoglund, G., Holst, B., & Lukešová, H. (2020). First experimental evidence of hop fibres in historical textiles. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12, 214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01171-6

Skoglund, G., Suomela, J. A., & Räisänen, R. (2025). A heritage “nettle” sheet reveals the first physical evidence of a hemp/hop textile from Denmark. Textile. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2024.2439707

Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. (2010, August 13). Recreated patterns of Zakopane bobbin lace [Odtworzone wzory – wprowadzenie]. Zakopiańska Koronka Klockowa. https://koronkaklockowa.wordpress.com/2010/08/23/

Zee, M. (2023). The effect of different retting methods on hop (H. lupulus) fiber quality for small-scale textile production(Master’s thesis, University of Idaho, College of Graduate Studies).